I tend to be deeply influenced by the books I read. So last week when I was rereading a bunch of books about eating locally, I thought to myself, “These authors are right! It’s crazy for me to be eating an orange that’s been shipped hundreds of miles or lettuce that’s come all the way from the west coast.” Surely, I could find a way to reduce the amount of fossil fuel expended to feed the gang of hungry people at my house.

I immediately imagined myself growing all the food we need right here, in my own backyard. I mean, I read

Farmer Boy over and over as a kid: I figured that qualified me to be a farmer.

I went outside to turn over the small vegetable garden behind the house. Obviously, I’d have to expand it. Right now, it’s only 12 feet by 24 feet, not enough to feed a houseful of Ultimate-playing young men.

After a couple of hours of working in the hot sun, the humid air and effort making me look like I’d entered a wet t-shirt contest, I tossed the shovel aside. Maybe I needed to convince my sons that gardening was more fun than Ultimate, and they could do all the work.

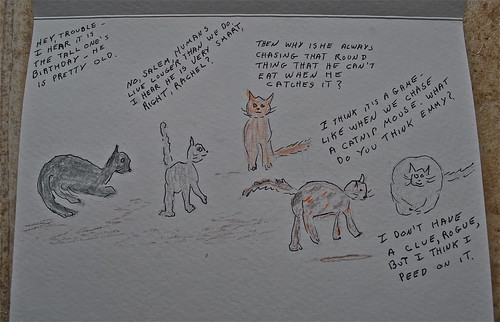

That possibility was as likely as me winning the lottery. My sons put 200 percent into anything they care about, whether it be Ultimate, jazz music, or physics. But that kind of intensity only extends to the passions they’ve chosen. I saw no sign that the highly theoretical physics research that Boy in Black does could be turned into a desire to farm, or that the hours that the younger two spend at the piano could suddenly be channeled into hoeing weeds. My husband wasn’t even an option: he’s at work in the daytime, and hordes of mosquitoes make evening gardening a type of blood sacrifice.

The solution, it turned out, was simple. I searched the internet for a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) farm. The closest one to me was less than four miles away: in fact, when I looked at the address, I realized that I’ve driven past the farm hundreds of times. I sent a frantic email to the farmer, saying, “I know this is really late to be asking, but can I buy a share for this season?”

An email chimed in only minutes later. “Sure, send us a check; we’ll have a bin ready for you this Tuesday.”

That’s the way it works. People like me, who simply don’t have the time to raise their own food, pay up front. Then for the next 26 weeks, I can stop at the farm every Tuesday afternoon on my way home from my piano lesson -- and pick up my bin of vegetables. We’ll get whatever is in season, whatever has grown well, and we’ll figure out how to make it into meals. If they give us too much dark green stuff, I’ll send it over to my mother, who would happily eat collard greens every day.

The best part is that I don’t have to do the planting, the hoeing, the weeding, the worrying about whether or not we’re going to have another frost. I don’t have to convert my geeky sons into farmers. And I won’t have to feel guilty when I eat delicious meals from food grown less than five miles from my house. Since the farm is on my way home, the amount of fossil fuel used to transport the food will be zero. I wish all decisions could be that simple.